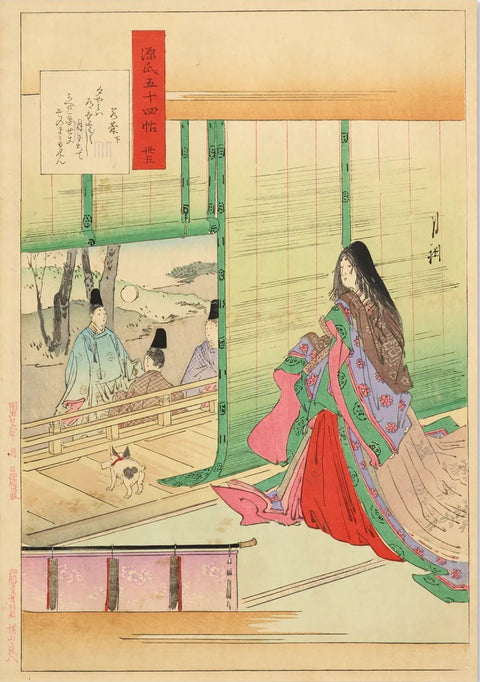

Wakana Ge. Chapter 35

Regular price$275.00 Sale price

Full Title: Wakana Ge. Chapter 35

Date: C1898

Artist: Ogata Gekko (1859 - 1920)

Condition: In good condition.

Technique: Woodblock.

Image Size: 237mm x 347mm

Description:

Chapter 35 from Ogata Gekko’s, Fifty Four Chapters of Tale of Genji.

The Tale of Genji was written shortly after the year 1000 in Japan’s Heian era, when the capital was situated at Heian-kyo (present day Kyoto).

On the last day of the Third Month there was a large gathering at Rokujo mansion. Kashiwagi had decided to go thinking that he might feel less gloomy to be near to the Third Princess. All the court people had also participated in the archery competition. Evening came, a pleasant breeze made the guests even more reluctant to leave the shade of blossoms. A few of them had too much to drink. The two generals, Higeguro and Yugiri, joined the other officers in the archery court. Kashiwagi was lost in thought. From time to time he would look vacantly up at the trees. Yugiri noticed and was worried about him. Then four years went by uneventfully. The reign was now in its eighteenth year. On the occasion of his illness, the emperor withdrew to his crown prince. The son of the Akashi princess became the crown prince. The dream of the Akashi people had nearly been accomplished. Genji went on pilgrimage to thank the god of Sumiyoshi with the Akashi people and Murasaki. It was late in the Tenth Month. The refrain of the Kagura music “Thousand years” continued in front of the shrine covered by a flowered tapestry, which was spread against the evergreen pines for the whole night to summon limitless prosperity for Genji. Genji had given lessons of koto to the Third Princess so as to be appearing grown up at the celebration of the jubilee of the Suzaku emperor. On the 19th of the New Year, he had a female concert for the rehearsal. The lady Akashi played the lute, the lady Murasaki the thirteen-stringed koto, the Akashi princess the sho piper and the Third Princess the seven-stringed koto. It looked like the magnificent concert symbolized the glory of the Rokujo. But, on the following morning — maybe she was relieved to see the orders in Rokujo – Murasaki had a high fever and a dark change began. The disease of Murasaki was heavy. Genji was at her side all the day. On the other hand, Kashiwagi was still thinking of the Third Princess. Guessing that the Rokujo mansion would be deserted, his yearning had grown stronger. It was the eve of the Kamo festival when he succeeded in entering her bedroom. But his feeling was far from simple happiness. Out of passion, it was a terrible thing to betray Genji whom he respected. A feeling of guilt overwhelmed him. The Third Princess was not well because of her sin. Hearing the report of her illness, Genji came to see her in Rokujo. Then a messenger came from Nijo residence that the lady had expired. He rushed off. At Nijo, the priest was leaving. Genji prayed to let her stay just a little longer and asked the priest to pray again. As though his intense prayer might have reached to the Buddha, the evil power of the late Rokujo lady disappeared. Murasaki narrowly escaped death. When the flower of lotus was full in bloom, though Murasaki was ill in bed, she could have her hair washed. It was only a rare occasion that she could raise her head a little bit. It pleased Genji very much. There were tears in his eyes. “I as almost afraid at times that I too might be dying.” Though he felt no great eagerness to see the Third Princess, it was not allowed him to neglect her because of the present emperor and Suzaku Emperor. At last, the ceremony of the visit of the Suzaku emperor was decided in the middle of the Twelfth Month. Preliminary rehearsals were conducted. As Genji knew of the relation between the Third Princess and Kashiwagi, Kashiwagi was reluctant to visit Rokujo. Persuaded by his father, the Minister (To-no-Chujo), and strongly invited by Genji, he set out. In front of visitors, Genji talked to him amiably, which made him uncomfortable. Losing the will to live, Kashiwagi contracted a fatal disease on returning from the preliminary rehearsal. Though Genji’s manner was jocular, each word seemed to Kashiwagi a sharp blow. Genji fiercely surveyed Kashiwagi. Lamenting his life, which went differently from his wish, he still thought of the Third Princess. In his letter he pleaded to her to write him even one word of pity. Finally, the Kojiju, who was a servant close to his house, delivered an answer. He sent for a lamp and read the princess’s note that said only, “You speak of the smoke that lingers on and yet I wish to go with you”.

Artist:

Ogata Gekko (1859-1920)

Gekko’s was born Nakagami Masanosuke in the Kobayashi district of Edo (Tokyo), and lived most of his life in the same district. His father was a wealthy merchant who ran the family business which had been established for several generations.

Gekko was orphaned at the age of 16 when his father died and his family lost their businesses and had to open a lantern shop. The teenage Gekko survived by designing rickshaws and selling his drawings. His rickshaws were shown at the Interior Exhibition of Industrial Design as examples of fine contemporary craftsmanship.

After this and after producing an immense number of paintings and sketches, he was recognized by such important figures as the artist Kawanabe Kyosai (often credited for ‘discovering’ Gekko) and the famous Ogata family, direct descendants of one of Japan’s most celebrated artists, Ogata Korin (who was himself older brother to the legendary artist, Ogata Kenzan). Ogata Koya adopted him and the young artist appended their family name to the name he gave himself, Gekko, which means ‘Moonlight’.

Though Gekko would later become a founding member and developer of several important art institutions, including Nihon Bijutsu Kyôkaï, Nihon Seinen Kaïga Kyôkaï (the Japan Youth Painting Association), the Academy of Japanese Art, the Bunten (the Ministry of Education’s annual juried exhibition), and an actively participating member of the Nihon Bijitsuin and the Meiji Fine Art Association, he never attended art school himself, nor did he undergo the traditional apprenticeship in a print maker’s studio. In a society that discouraged self-promotion, Gekko began his art career by preparing flyers and taking them around to various publishers and places to sell his services as an illustrator for magazines and newspapers and a designer of lacquerware and pottery.

Although his techniques were thoroughly modern, Gekko considered himself to be firmly rooted in the ukiyo-e tradition. Though he had no teacher himself, he had some outstanding pupils during a 30 year teaching career, including Yamamura Toyonari (Koka), his son Ogata Getsuzan, Kanamori Nanko, and Tsukioka Kôgyo (1869-1927), whose mother had married the Meiji Period’s other great artist, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi.